The account of the excavation of Alnwick Abbey begins with the discovery of a medieval grave slab during drainage works. The Alnwick Mercury of 12 July 1884 reports: ‘At the last monthly meeting of the Newcastle Society of Antiquaries, the Rev Dr Bruce … read the following notes on the discovery of a grave cover at Alnwick Abbey: A few days ago I was informed by Mr Reavell, resident architect of Alnwick Castle, that in cutting a drain in the Abbey grounds he had come upon a tomb which he asked me to come and see. … His Grace the Duke of Northumberland has given orders for a complete examination of the foundations of the abbey buildings to be made.’

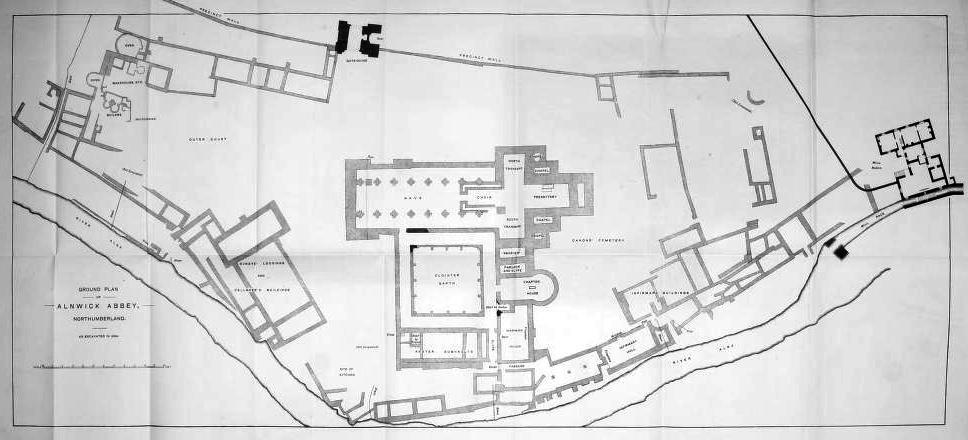

Initial results were disappointing, largely because the work was initially centred too far north of the claustral complex, but later in 1884, the Duke of Northumberland sought the advice of the antiquary, William St John Hope. The cloister and church were soon located and later that year a ground plan of the entire abbey complex had been made. Hope and Reavell went on to investigate and record most of the abbey precinct.

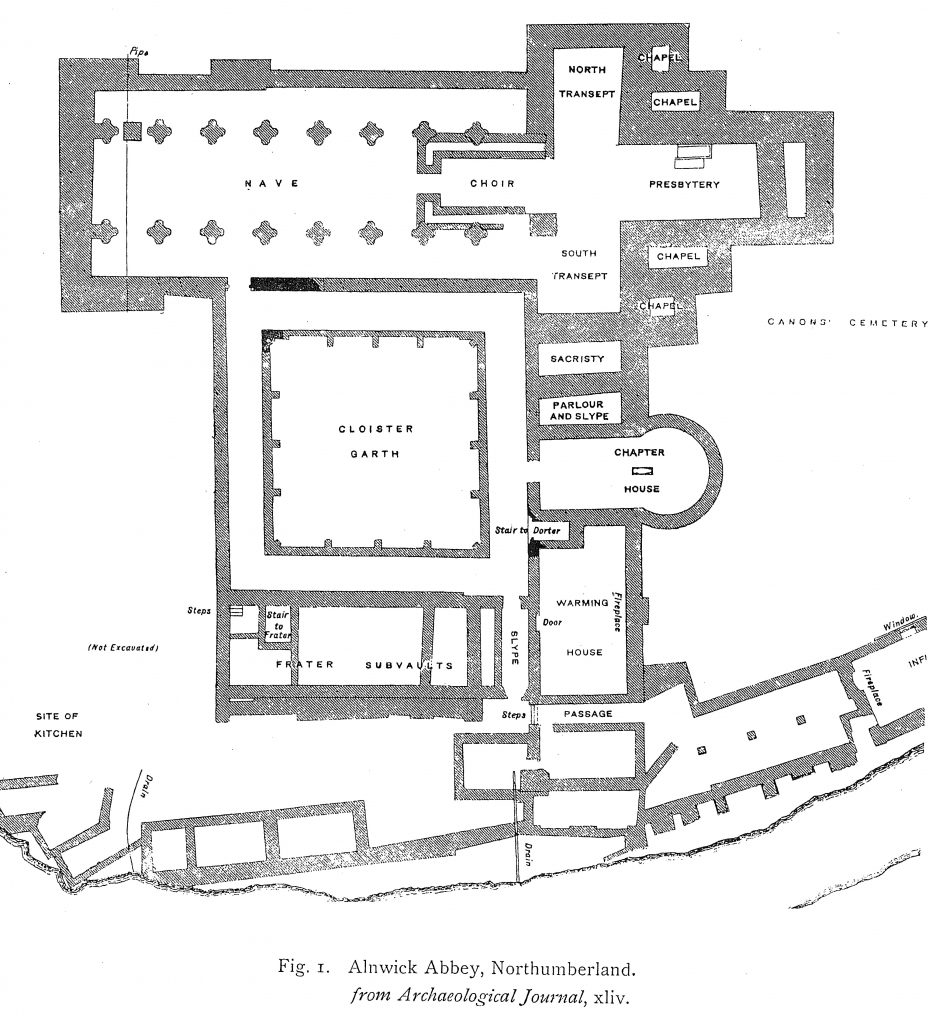

Hope published the results of the work at Alnwick in the Archaeological Journal in 1887 (Vol 44, pp 337-346) and published virtually the same paper again in 1889 in Archaeologia Aeliana (Vol 13, pp 1-10).

The key points from the excavation report are as follows:

- Stone robbing and clearance had been extensive and thorough and at the start of the excavation, with the exception of the gatehouse, ‘a perfectly level green field lay between the gatehouse and the river Alne where the abbey … had formerly stood’

- The site of the abbey is roughly semi-circular in plan, a boundary wall forming the diameter (in which is set the gatehouse), and the river Alne the circumference. The abbey church stood in the centre of this, area, with the cloister and surrounding buildings extending southwards to the river. On the east lay the infirmary, and on the west the outer court.

- The church was cruciform in plan, consisting of a nave and aisles of eight bays; north and south transepts, with two eastern chapels to each; and a presbytery of four bays. … Of the nave enough was found to make the arrangements pretty clear. The two easternmost bays formed the conventual choir, and retained the parallel walls on which the canons’ stalls stood, returned, as usual, at the west end. These walls were a little over 2 feet apart, the intervening space being paved. The width in the clear between the stalls was about 13 feet.

- The church appears to have had a central tower, though apparently one of no great size.

- In the westernmost bay of the north arcade was found a square base about 4 feet square. Under its western edge was a lead pipe, which was traced north and south across the whole width of the church (see plan).

- The cloister itself was 90 feet square. The surrounding alleys were 11 feet 9 inches wide, and paved with flagstones, some of which we found in situ. [The church was paved with similar flagging.] The wall enclosing the garth was divided into four bays on each side by buttresses, and had an additional diagonal buttress in each corner. Some portions of the original arcading that stood on this wall were found during the excavations; they consisted of beautifully wrought twin capitals and bases, the former richly carved with characteristic early-English foliage. This arcade was an open one, and unglazed.

- To the south … was the capitulum, or chapter-house. In plan this building is perfectly unique. It consists of a rectangular western portion or vestibule about 30 feet 6 inches long, and 21 feet 7 inches wide, opening on the east into a circular portion 26 feet 10 inches in diameter, the whole being about 50 feet long. This extraordinary chapter-house cannot be later than the early-English period, and is probably earlier … A stone coffin containing bones and without a lid was … laid bare in the centre of the round part of the chapter-house.

- On the south side of the cloister, and parallel with the church, were found the foundations of the substructure of the refectorium or frater, which here, as in other canons’ houses, was on the first floor. At the east end of this range was a narrow slype leading from the cloister to the buildings by the river, and towards the west end a small square chamber marked the site of the stairs up to the frater; the rest of the substructure was used as cellarage.

- Alnwick abbey differs in one important point from most monastic houses, in that there is no range of buildings on the west side of the cloister. This part of a monastery, …is always occupied by the cellarage, and lodgings for guests under the cellarer’s charge, and hence known as the cellarium. A diligent search, however, failed to bring to light any traces of a western range here; and it is probably represented by the large block of buildings a short distance to the west on the river bank.

Stone robbing and clearance had been so extensive that very little evidence for detecting phases and alterations to the building could be noted Hope comments: ‘The whole of the walls east of the nave had been removed down to the foundations, and it was quite impossible to learn from these anything except the block plan’. The only phasing evidence quoted, is the possible extension of the nave westwards as part of a phase of rebuilding.

The excavated area was left open for a while but seems to have been covered over again by the end of 1885. There are several reports in the Alnwick Mercury of the visits of learned societies to view the exposed foundations during that year. When the trenches were backfilled, the building lines were marked out in the pasture: ‘the Duke has caused the lines of the walls, etc., to be permanently marked out on the surface of the ground by an ingenious application of concrete.’ This marking is now buried and no longer visible although, in dry years, it can still be seen as parch marks in the grassland.

The full text of St John Hope’s report has been made available by the Alnwick Local History Society and may be accessed HERE