ORIGINS & FOUNDATION

There can be little doubt that the island of Oxney represents a ‘special’ or sacred place. There is an extensive (and largely undisturbed) Bronze Age barrow cemetery just 0.5km to the south east and Everson and Stocker (p.399) suggest that the fen island may have been an important location for seasonal gatherings, perhaps incorporating markets and exchanges, from prehistoric through to early medieval times.

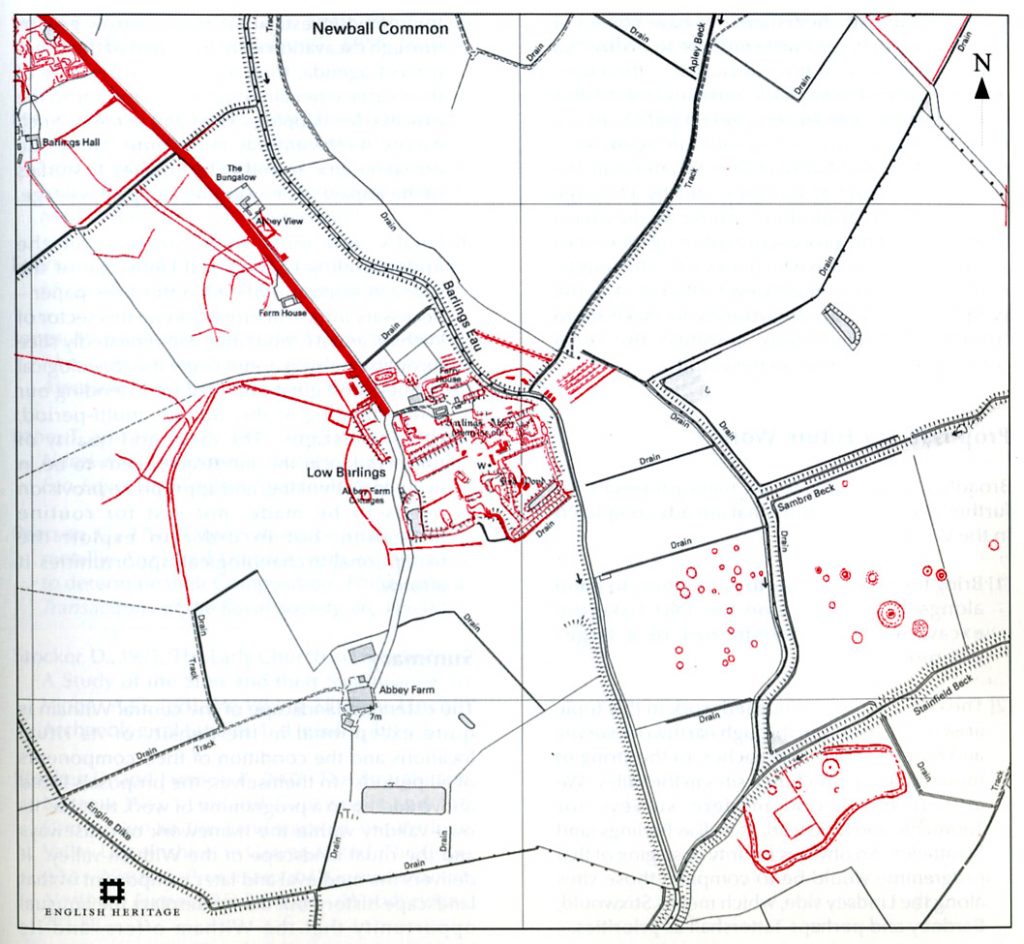

The illustration shows HER data over the Oxney island base map and emphasises the concentration of early ritual monuments in the fen around Barlings Abbey.

There may also have been an early chapel here, and E&S (p.399) comment:

‘ The only separate chapel we hear of during the medieval period on Oxney, additional to the abbey itself, was that dedicated St Eligius or Eloi, patron of smiths and metalworkers. Such a saint, we might argue, would have held particular appropriateness to the exploitation of the woodland resources that went with the island’s location. But we might also wonder whether Eligius had been chosen to sponsor a market place where such workers’ goods were traded. The saint was additionally renowned as a preacher: a characteristic which might have appealed to the Premonstratensians.’

Whatever the attractions of Oxney island, it seems clear that the initial foundation was at Barlings Grange on the slightly higher fen edge to the north west. Everson & Stocker (p.133) note that there had been a Benedictine alien priory at Barlings Grange, which was later gifted by Ralf de Haya to the Premonstratensians. This was possibly intended as a temporary home during the construction of the conventual buildings at Oxney.

A 13th century cartulary survives for Barlings (BM., Cotton, Faust. B. i.) but as Colvin (p.70) notes, ‘Owing to the unfortunate mutilation of the Barlings Cartulary, which is imperfect at both ends, the texts of the charters relating to the site of the abbey and to its initial endowment have been lost, and only the general tenor of the foundation charter can be recovered from later confirmations‘.

At the site of Barlings Grange, St Edward’s church (now the parish church) has a surviving portion of Norman fabric at its west end, which may represent the first abbey church, before the convent’s move to Oxney . . . or it may be part of a grange chapel from the abbey’s main period. There is a detailed analysis of the fabric and phasing of the building in E&S pp. 115-141.

Ralf de Haya, son of the constable of Lincoln Castle and lord of Burwell and Carlton, founded the Premonstratensian abbey of St Mary of Oxney at Barlings in 1154 with an endowment of the place called Oxney, for the construction of the abbey. He also gave the whole vill of Barlings and its appurtenances, but excluded the hunting park there and the meadows.

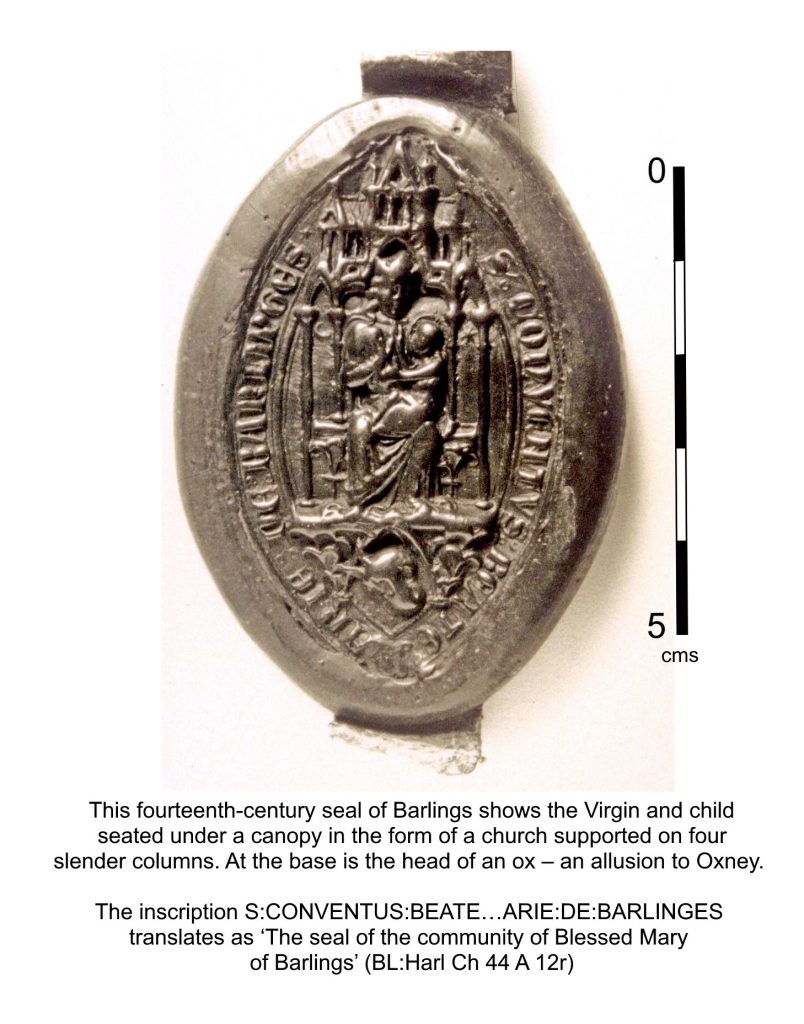

The initial community that established itself on Oxney around 1154/55 comprised thirteen canons from Newsham, amounting – as the special bond of fraternity between the two houses in 1310 recalled – to a half of Newsham’s complement in the mid twelfth century (Colvin 1951, 70 citing BL, Harleian Charter 44H16). The church of St Edward Barlings was soon added under a settlement with the owners, the abbey of Lessay in Normandy, and was included in Henry II’s confirmation. So, too, were other early gifts in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, made by other de Haya family members and their tenants, and a hunting park and meadows at Barlings itself.

HISTORY

The ‘island of Oxeney’ and the vill of Barlings were in themselves a very moderate endowment for a community of thirteen canons, but the new abbey was fortunate in attracting substantial endowments during the first hundred years of its existence, so that in 1543-35 it alone among the Premonstratensian houses in Lincolnshire enjoyed an income of over £200. At that stage, the abbey’s properties included the churches of Scothern, Reepham, Stainton by Langworth, Swaton, and Bungay; and the manors of North Carlton, Caenby, Glentham, Scothern, Swaton, Market Stainton, and Snelland.

During the mid-fourteenth century, two abbots (Thomas and Alexander) were under the special favour of the king (Edward III) and of Queen Philippa, and were exempted from various taxes in order to facilitate the rebuilding of the abbey church.

In 1412 it was stated that there were about twenty-seven canons in the monastery, but its revenues were so diminished by poverty, debt, and the burden of hospitality, that they could scarcely be sustained, and they received an indult allowing them to celebrate private masses (called ‘annuals’) in the abbey church which were purchased by rich patrons.

It seems that the abbey recovered its prosperity somewhat during the fifteenth century, as Bishop Redman praised the administration of the abbot (see visitation reports below) and noted in 1500 that Barlings was: ‘in an excellent condition’ with a ‘good temporal state’.

Visitations of Barlings

10 June 1478 – Bishop Redman finds all in good order : abbot is to find for each priest a pension if 20 shillings a year; canons ordered to wear almuces under their cloaks and to make deeper inclinations in choir; not to frequent inns nor to indulge in excessive drinking within their house.

31 July 1482 – The abbot is newly created: he is enjoined to see that women are kep out of the monastery precincts : he is to watch against the introduction of new fashions in dress, and in particular what are commonly known as ‘korkes and patans’.

3 September 1491 – Bishop Redman severely punished a canon charged with incontinence, and another with apostacy. He again warns the community against the introduction of new fashions in dress.

20 September 1494 – Bishop Redman praises the temporal administration of the abbot ; issues orders as to the provision of proper almuces : condemns the use of wide shoes, called ‘slyppars’ : regulates some church customs.

10 September 1497 – Bishop Redman finds the house in a good state : gives directions as to the correction of faults

18 November 1500 – Bishop Redman finds the abbey in an excellent condition : the good temporal state seems to be a reward for the good observance.

Barlings abbey would have survived the first Act of Suppression on account of its sizeable income, had it not been for the abbey’s alleged involvement in the Lincolnshire Rising. However, Abbot Mackarel was clearly not confident that survival would be long-lasting and he had taken steps to cover emergencies by secreting about £250 in money and £100 in plate, vestments &c., so that he and his brethren might not be left destitute in the event of dissolution.

Following the Lincolnshire insurrection of 1536, when Mackarel was a prisoner in the Tower, he confessed to having taken these precautions and admitted that he had gathered his brethren in chapter and advised them to do likewise.

There were allegations that Abbot Mackarel was the ringleader of the Lincolnshire Rising (Captain Cobbler), but there is no evidence whatever that he and his convent were anything other than unwilling participants, providing food and lodging to the mob under threat of violence.

Mackarel stated that ‘On the morrow, being bidden to join the host, he refused on the ground of his religion, but offered to go and sing the litany for them. By Friday, after news that several of the neighbouring gentry had been compelled to join the host, he took provisions to them on a large scale, and on Saturday sent six canons.’

By Sunday, 15 October, Abbot Mackarel and six of his brethren were lodged as prisoners in Lincoln Castle. … he himself was sent up soon after Christmas to the Tower. He was examined there twice, on 12 January and 23 March, but neither there nor in Lincoln ever admitted to having aided the rebels any more than their violence compelled him to do. He said he would have fled at the beginning of the rising, but that he feared for his house and he denied repeatedly having bidden the host to ‘ go forward.’ He had indeed promised to bring more provisions later in another place, hoping thus to make his escape. … finally, on 26 March, 1537, he with six others was condemned to death, and suffered the extreme penalties of the law.

A contemporary report of the execution states: Also this yere the xxv day of March the Lyncolnchere men that was with bishoppe Makerell was browte owte of Newgate un to the yelde-halle in roppys, and there had their judgement to be draune, hongyd, and heddyd and qwarterd, and soo was the xxix of March after, the wych was on Maundy thursdaye, and all their qwarters with their heddes was burryd at Pardone church yerde in the frary.’

Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London, 1537, 53:40

DISSOLUTION

Barlings was not dissolved in a routine process – its status as a ‘traitorous and attainted house’ led to its early closure when it might otherwise have been expected to survive. The nearby Cistercian house at Kirkstead shared this fate with Barlings.

Special care was taken to assess and dispose of its possessions. Robert Dighton of Little Sturton and Thomas Dymoke of Scrivelsby, local loyalist gentry, were commissioned in May 1537 to make an inventory of the goods of Barlings Abbey under the direction of Sir William Parr. It is said that the lead stripped from its roofs valued more than £400 and it was noted that: ‘more than a horse load of the Abbot’s books were carted away’.

The King granted Barlings and Kirkstead to Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, who had been instrumental in putting down the Lincolnshire Rising. The lands formed a power base for Brandon as the leading nobleman in Lincolnshire. In addition, the king granted parts of the abbeys’ lands to Sir Edward Clinton, Earl of Lincoln.