Following the seizure of Barlings in the wake of the Lincolnshire Rising, the King granted the abbeys of Barlings and Kirkstead to Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk; he had been instrumental in suppressing the rebellion. Brandon died in 1545 and his Lincolnshire estates were split between his three female heirs. However, Barlings Abbey was later to be returned to the crown following the execution of Jane Grey in 1554. At that time, the Barlings Abbey precinct was described as containing: ‘houses and buildings . . . called “le Abbottes lodging”’ and it seems likely that Brandon had developed an existing abbot’s lodging into a fashionable country house.(E&S p.95).

The house at Barlings does not seem to have been much used during Elizabeth’s reign. In 1609 the property was transferred to the Earl of Hertford and then, in 1610, sold on to Sir William Wray, when it was described as ‘the capital messuage and scite of Barlings and all lands tenements and hereditaments belonging to the late dissolved monastery’.

Sir Christopher Wray (1601-1646) brought his wife, Albinia (daughter of Edward Cecil, Viscount Wimbledon), to live there following their marriage in 1623. It is thought they renovated the house that Brandon had created from the Abbot’s lodging.

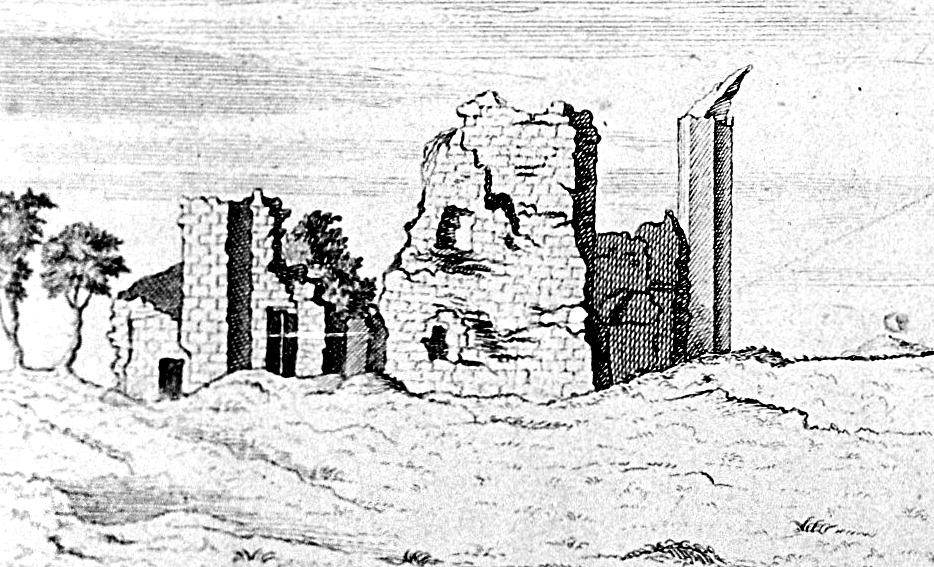

In the 1660s the house passed to their second son, Edward Wray, and at his death in 1684 his inventory gives a room by room description of the building. The ruins of this mansion may be seen on Millicent’s engraving of Barlings of c.1730 and Everson and Stocker have been able to locate the site of the house in the surviving abbey earthworks and also to attempt a reconstruction of the layout of the rooms based on Edward Wray’s inventory (E&S pp. 96-109).

Millecent’s drawing of c.1730 clearly shows the house in ruination and the building materials, as with those from the abbey itself, were doubtless soon redistributed and reused in buildings in Barlings and Langworth villages.

The abbey precinct and the ruins of the claustral buildings became the setting for the post dissolution house and gardens, however the western portion of the church (the nave and its north aisle) survived demolition and was retained as the parish church for Barlings – seemingly until around the 1690s.

The antiquary Abraham de la Pryme visited Barlings in 1697 and recorded: At Barlings, five miles of this side Lincoln, was in antient times a famous monastry. The church was left standing, but with all the lead of and the bells gone, which church [is] now standing, tho’ in rubbish. Yet in the same is several monuments and inscriptions to be observed, as I heard this day.’

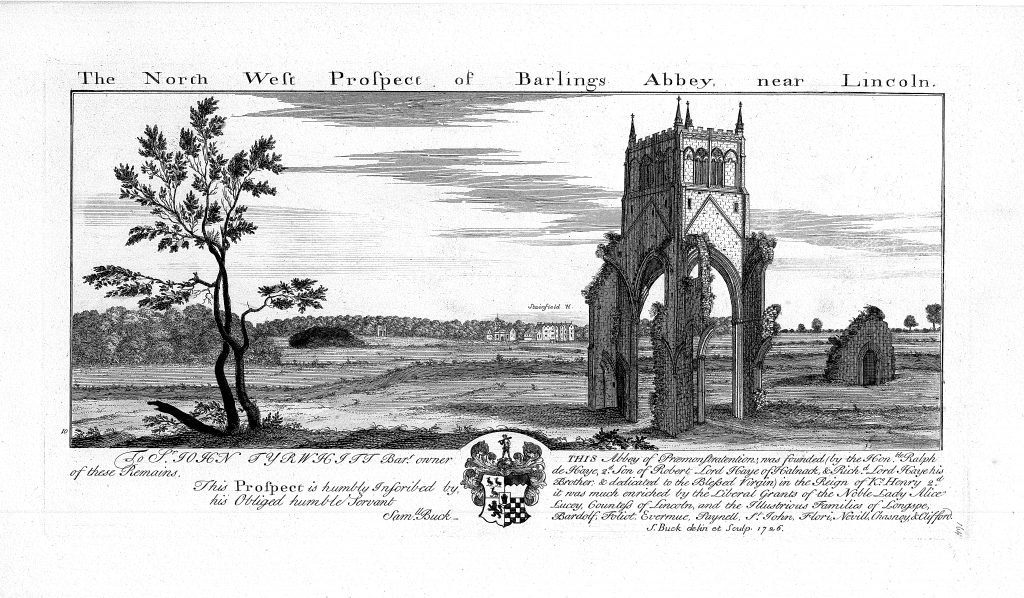

By the time Samuel Buck drew the site in 1726 all of the stones of the nave had been removed leaving only the central tower – probably retained as a landscape feature by Sir John Tyrwhitt who then owned the site. It is likely that Tyrwhitt built a new church at Stainfield and demolished the ruined nave at Barlings.

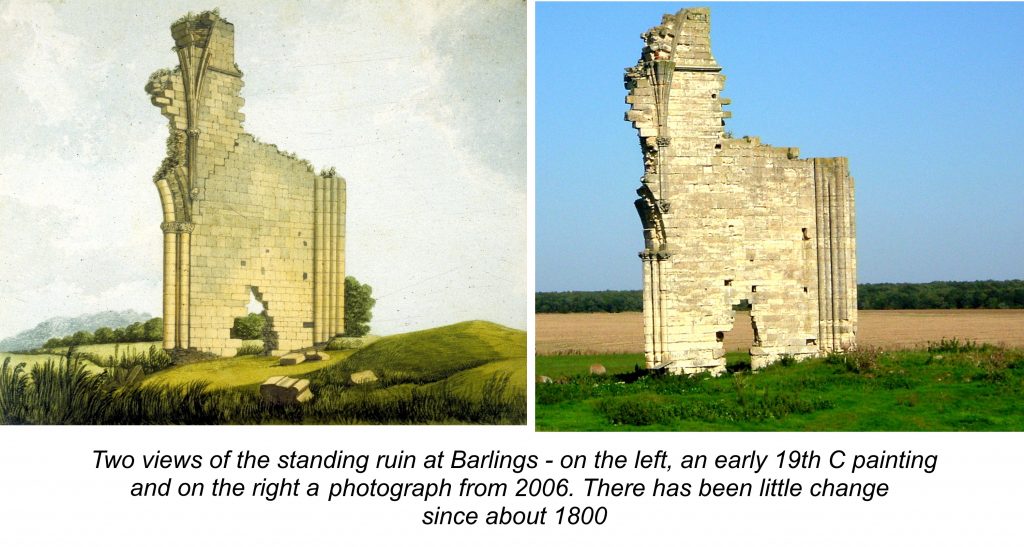

The tower finally fell in 1757 and John Byng, visiting in 1791, noted ‘they are daily carting away the stones’. Attempts were made to demolish the last standing fragment in the early nineteenth century but thankfully these were unsuccessful and the last fragment of the ruins of Barlings Abbey still stands.